The Details of Death - Preparing an "In Case of Death" Box: Yet Another Legacy of Keith Drury

One year later, I reflect on a uniquely helpful system my Father prepared for us in handling the details involved after a loved one dies.

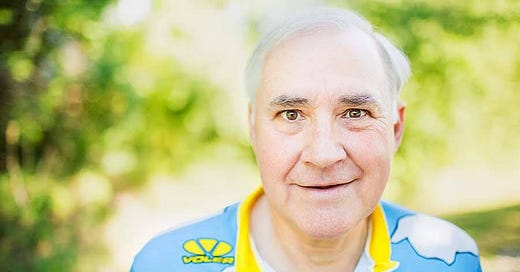

One year ago, my father, Keith Drury, just wasn't himself at the end of a Sunday morning church service. After making it home, an ambulance took him to the hospital with stroke-like symptoms. In less than 12 hours from the first thoughts that something might be wrong, he was already dead. The official time of death in the records was 10:39 p.m. on April 7, 2024, and I am sending this to you exactly one year, to the minute, from that moment.

We were shocked. Blown away. How could this be? Already? Gone too soon.

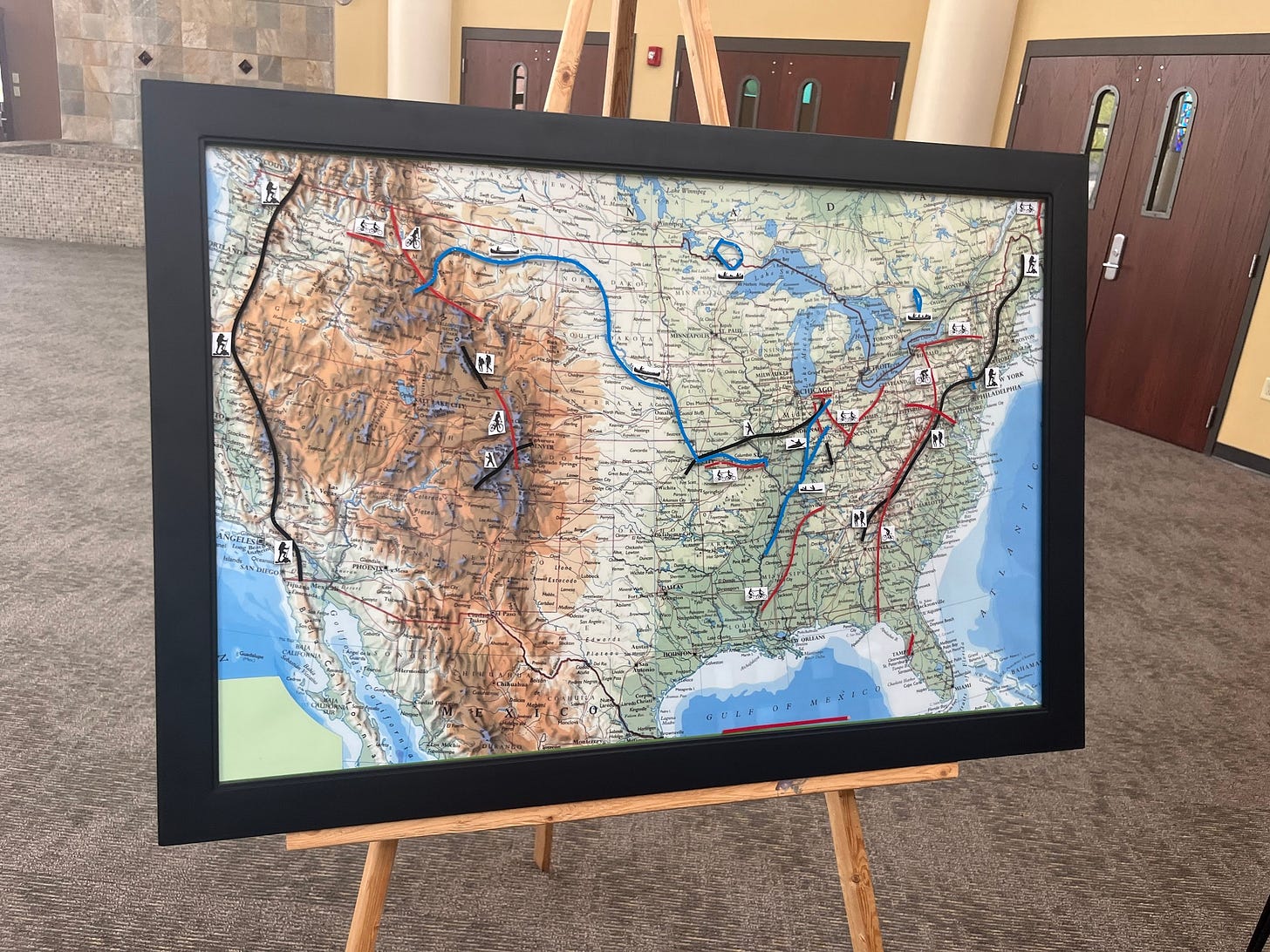

While Dad was the kind of person that many saw as a wise sage they would seek out for advice, he also usually seemed younger than he was. He often engaged in activities others decades his junior had given up. When I was young man, I hiked the “Presidential Range” portion of the Appalachian Trail with Dad, just the two of us. I could barely keep up. Of course, he had been hiking for three weeks in "thru-hiker shape" and I was more in "reading the Reformers all day in a grad school library basement shape." But I was still in my early 20s and he was in his early 50s! In other cases he did things far earlier than others had—an early adopter and forerunner. In either case, he was known for doing things at an age he shouldn't have.

He really shouldn't have died at the age he did either. He had so much more to give. He had a lot of great friends, and was a great friend to others. He had timeless wisdom for his many email pen-pals and mentees, even a few that would sojourn to find him in retirement for advice. His mind was still super-sharp. He wasn't the physical specimen of his earlier decades, but he could still work around the house and yard and do things many half his age hire others to do. But Dad tended to do things at an age he shouldn't have, including dying.

The details of death

Dad was always ripe for a challenge. He was even competitive with himself and others about recovering from surgeries. He tracked data and health progress in the months after a surgery recovery like others track and train for marathons. So perhaps he could have taken on the challenge of a post-stroke life. However, we all wonder if that challenge might have been too much for a guy wired up like him. We didn't want him to die, but ultimately, grateful he went so fast, even if most of us didn't get to say goodbye.

My brother and I, in shock and task mode, rather than truly grieving yet, hopped on the same plane in Indy to get down to Florida and be with our mother, Sharon Drury. All who walk through this know what those days look and feel like. They are hard. They are intense. There is so much weight on your heart. It is hard to sleep. But then again you're so exhausted all you want to do is sleep. You're happy to hear from people but have an instinct to not talk with anyone. It is intense and quite private. Grief can be shared, and yes, the support of a community can provide solace. But part of grieving the loss of someone is a journey one must pack for, carry the burdens of, and walk through... somewhat alone. Some of the aloneness is the point. Your loved one left you alone, in a way, not others. And alone, we grieve.

But together, we heal. The family rallied around one another. So many amazing local friends showed up to help—some of the best friends my parents have ever had. We all tried to step up to not only be there for Mom but also to help with the details. Because, man alive, there are so many details!

Death in every culture has a lot of extra stuff to manage beyond the grief. Several of my Muslim friends have a tradition that when your family member dies, you are then expected to host people at your home for a full week after. People show up to offer their condolences at your home, and you serve them tea and snacks and sit with each other for an hour or two. You do this for nearly everyone you know—because it's expected that people show up.

In our culture, I know many people who understandably don't want to have to greet people at a visitation or viewing for their loved one, much less have the wherewithal to host people for a full week at their home immediately after their death! While it is always nice to get a plate of cookies or a pie, some other parts of our traditions in grief often make things worse, not better. In the United States, hosting people is not usually the primary problem we have to cope with. Instead, the way the world makes things worse for us is as follows, spoken in the persona and voice of "the World" saying this to you, even if no human says it this explicitly:

"Hey, this is the World calling. I know that person you love and were deeply committed to just died, but it’s time to get after that To-do list, okay? First, the World needs you to make tons of financial, legal, and insurance decisions. These include decisions about the actual body of the person you love most that you have lost. Following that, the World needs you to plan out a worship service. At that event you need to greet all the people who will show up. In addition, write a little newspaper-like article about your beloved that will be posted on the internet tomorrow. Thanks!"

Of course, nobody says any of this to you. And I am not complaining for myself as much here as for others. My family and I might be particularly good at a lot of these things compared to many, as we are used to planing worship services and writing things and other such examples. I share it mostly to just empathize with all the details people feel they have to do right away.

I suppose you could shirk off all this and do none of it. Perhaps it would be fine if you didn't do all those details that week. Maybe it would all handle itself? Or maybe part of how we grieve is having a task to do—indeed that sounds a lot like us in our culture too. However, you do feel this pressure. You think: there is SO MUCH to do. But what to do first?

Productive, even after death

Here, even beyond this life, Keith Drury showed up to help. Few people knew how to make stuff happen like Dad. He was a productivity beast long before all the productivity gurus started YouTube channels or read Getting Things Done or Managing Oneself. He was getting things done before anyone knew what "flow" was or engaged The Four Disciplines of Execution. I know some ambitious young students (and more than a few fellow professors) who learned more from the way he taught than what he taught. The same could be said for his decades in another previous life while doing denominational work.

So, of course, Dad, known for doing things at an age he shouldn't have, was here teaching us about how to manage the details of someone's death, even during the week he had died.

Dad left us an "in case of my death" box. It was in an old school leather catalog case, the kind people used back in the 1970s. There were many "transparency" boxes in there (the kind most people under 35 would not even recognize). Each had a different label on it: finances, health, taxes, etc. But there was one box labeled "In case of my death."

In the first days of our grief, as we sat down at the kitchen table, we three from the immediate family opened up that catalog case, and asked the question: "What do we have to do now?"

The beautiful thing is that Dad left us with the gift of answering that question for us. I'm sharing this with you now, a year after his passing, as a way of honoring that service to us, because Dad was teaching us about the details of death even the week he died. I've shared of this box with others in conversations since then, and every time they say in return: "Oh man, you need to write that up for others."

So here goes. Below is a list of things my Dad had in his "in case of my death" box. This is not a comprehensive list of all one should or could do. I merely know we wouldn't have thought of a bunch of these things without the checklist, so perhaps it's helpful for you as well:

The Contents of Keith Drury's "In Case of Death" Box:

#1A - Durable Power of Attorney

#2B - Our Personal Attorney

#1C - Combination Living Will and Designation of Heath Care Surrogate

1) Funeral (including preparation of body and services)

2) Previous Wills

3) Passwords

4) Finances

5) Copies of important documents like deeds of property

6) Pension and related benefits

7) Life and any "death benefit" style insurance

Here below, you will see a two-page letter my Dad sent us, believe it or not just one week before his death. But it is key to know that he sent letters like this occasionally about his health, or when other details changed that would have an impact on the future. So this letter on March 31, 2024, didn't seem all that out of the ordinary for any of us. We weren’t taken aback by it. It felt nearly routined. We had no idea, neither did he, that he would have a hemorrhagic stroke (brain bleed) just a week later. I say all this to say that even if he had not sent this letter, so prescient now in retrospect, we would have been able to use previous letters and his "in case of death" box to guide us just fine. A lot of personal or sensitive information is omitted from this letter, of course….

Why this helps so much

So as you can see, what he did was not all that complicated. I think most any of us can do this. Perhaps my father was more comfortable bringing up death than most people and was willing to break the ice on the subject. And I have heard that sometimes men are more comfortable taking of death than women. I’m unsure. In any case, having his letters and seeing all the information he provided all in one place, physically (as well as saved online for us), was so helpful. Some of this may be obvious to you, but I want to add a bit of commentary on parts of the Table of Contents in case it might add context:

The Durable Power of Attorney documents my parents signed would have been key for us to have access to if there was a medical crisis where one of them was too disabled to make decisions (among other reasons); that would make it possible to transfer money or assets so it everything is not eaten up by other expenses at the end of life.

It was important to have some information on the funeral service itself and arrangements for the preparation of the body (as many make in advance these days). All of these decisions are so very difficult—and just having in black and white what a loved one wanted you to do is better than trying to remember what they wished or forcing you family to argue over "what you would have wanted." One key matter is getting death certificates for notifying pension accounts, social security, banks, changing property deed information, investments, medicare, and otherwise. After reading the list Dad gave us of how many we might need, we asked for 15 death certificates, just to be safe. We knew we needed 8 without a cause of death, and 3 with the cause of death. In this information, he also included who to notify in case of death—since he had made arrangements. It was also nice that he just "let us off the hook" in his expectations for the funeral/memorial service. Sometimes, too detailed of a plan is hard to make happen, and that can be stressor.

Having information on passwords is something many of us don't think of. Our phones are nearly impossible for even the FBI to break into; so don't think your family will be able to do so without your passwords. Same for your computer, and of course, the dozens, even hundreds of other passwords in your life. Managing this can feel like a part-time job for all of us, and if you want to save a loved one a whole lot of headaches, share these passwords in advance.

Dealing with the finances is a particular chore—and a lot of work can be done in advance as we age to prepare; and my Dad did a lot of this work for us. It was important to get a full listing of all income, all assets, all expected insurance, all benefits, and all pension information. The reality is that when one spouse dies the entire financial picture changes fairly quickly, even in retirement. I will say that my father was more concerned about this than perhaps he needed to be. He may have over-prepared, even. But it makes sense that he was concerned about my Mom’s finances once she lost some of his benefits up on death. Having a clear picture of the financial picture, as well as access to all these projections, was important, and it may be more important for others than it even was for us. The key on these matters is to have beneficiaries listed on every account or benefit we had, and that was handled well in advance.

It is important to note that having a health surrogate is needed for most everyone. Being able to make decisions for someone else in health situations is key, and keeping these updated when current contact info changes. I have witnessed that (as a pastor caring for families in hospitals) having clarity for medical personnel is not only important, but also key within a family for knowing on who is in charge. It is also helpful for the person making the decisions themselves, since it gives you confidence that your loved one really did want you to make the decisions involved. These choices are never easy, and because they are afraid of legal implications, medical personnel will not usually press for clarity on decision-making, so having this determined in advance is helpful.

So that's a little of how Dad continues to do things at an age he shouldn't, including in this case, coming out with an article about how to help your family cope with all the details after your death. In this case, he's doing it a full year after his own death, even for you.

Perhaps that makes you grateful for him. If you knew him maybe that makes you miss him today too. If so, join the club—we miss this man dearly!

What has your experience been in dealing with all the details involved when someone you love dies? How did you cope with all that needed to be done? What do you wish you were prepared for? What did you learn?

Thanks for sharing. Your Dad’s plan was excellent! One thing that wasn’t covered by a loved one who shared much/most of what was listed here, was a list of recurring, automatically billed subscriptions. Things like annual renewal of computer programs or online security accounts drafted from a bank account or credit card. These were surprises that came “down the road” in our case. And if you didn’t catch it on a joint credit card you had to go back cancel the subscription & justify a refund.

Even in death Keith provided a path for others. Thank you for sharing, such a KD characteristic duplicated in you. One of the joys of this new day is that geography does not create separation, I still miss your father more than words can express and the interaction we shared. His intuitive insights and prophetic foresight are great losses for which I have found no replacement. I often reflect, without Jesus Christ we would probably never have connected and what a loss that would have been.