It is Here: A Journey Among the Cultists and Prophets of Artificial Intelligence

Large language models, philosophical and practical suggestions about AI, and a cameo by none other than A. I. Gore

We need to talk about artificial intelligence. But first, a preamble regarding the words we use to discuss it.

We were playing a family game with our adult children. One of my daughters had to say out loud the name of a famous person on a card, and because of the way it was written, she blurted out, "A. I. Gore."

This way of thinking about the infamously wooden failed presidential candidate1 has cracked me up ever since. The idea that Vice President Albert "Al" Gore was powered by artificial intelligence all along makes me giggle, especially in light of his spurious claims of having "invented the internet."2

You might not know much about Al Gore, but "Al" is short for Albert, not short for Artificial Intelligence. Among the many quandaries of this Artificial Intelligence age, logophiles have to decide whether the term should be rendered as an acronym or initialism. If it's an acronym, then "AI" would do, much like FBI, NASA, or even YOLO. An acronym might also be preferable to the laborious typing of periods in an initialism such as "A.I." But then that leads to the aforementioned confusion between AI and Al.

For expediency's sake, I've decided that hereafter I will be using the acronym for artificial intelligence, sans periods, as most everyone does. However, if you ever think I'm talking about A.I. Roker or A.I. Pacino, I'm referring to the weatherman or the actor, respectively, not their artificial intelligence-powered robot successors.

Computers, the Internet, and Artificial Intelligence

In an earlier article, I claimed to be among the First Digital Natives. I outlined my history with computers, starting in around 1980 when my Dad bought a computer for the price of a new car. Because of this, and my daily use of the computer ever since I've never really lived without computers in my schooling and hobbies. I marched through all this personal history in reaction to the critique of Neil Postman, the author of the book Technopoly. I wanted to gain some personal awareness about the origin and effects of the technology I use, and to spur that along in others as well.

In a subsequent article, I talked about the brief window in time when the internet, not computers, actually started to change everything. In this piece, I continued my awareness related to technology by analyzing my own experience with the gradual (then sudden) internet revolution, with a bit of compassion for the digital immigrants among us, even if it came from an insufferable bore with a humanities degree like me.

In the first article, I included the subtitle, "How technology changed everything, three times and counting." This was a signal of my intention to lead up to this article about AI. Computers were supposed to change everything, and no doubt they did make possible all the rest of what we've discussed. But it was the internet that enabled computers to touch every part of our lives, the wheel's axis, as it were. We are now in a season where another revolution is upon us, a change that may be even more pervasive and impacting than the computer and the internet before it, and that is the advent and acceleration of AI all within the last several years.

Large Language Models

Like many of those who do not engage in computer programming on a daily basis, my first interaction with artificial intelligence came in early December of 2022, just days after the launch of ChatGPT, powered by a research preview of the 3.5 model. I was watching an NBA game, and it wasn't a very entertaining one, being early in the season and a blowout. I had heard of the launch of this AI app and went to the site and messed around with it.

The experience reminded me of my Dad setting up that first TRS-80 computer on our dining table back in my childhood, and also reminded me of when we accessed the internet the first time a decade later. In both instances, our sentiment, even verbalized, was "This will change everything." I asked AI a question. It only took a few seconds for the reply to come. I read it and then asked another question. Like many others in those first days experiencing what is called a "large language model" (LLM), I was astonished by what we now know was a quite early, even primitive version of what we commonly call artificial intelligence.3

I tried to test the limits of AI right away, during that first session, perhaps like you did. I immediately thought of how a 10th grader in High School might use this to cheat, so I asked the LLM to write an essay on a book I knew a lot about and read in school. The resulting reflection paper on the book was astonishingly clear and well done. I then asked it to write a poem that sounded like it was written by a 15-year-old during study hall (intuitively engaging, without knowing it, the “training” it turns out is key to good responses from AI). It promptly delivered a fittingly sophomoric rhyme that even included some awkward humor and connections a student forced to write a poem for the first time might use. I was blown away by the result. For the very first time in my life, I realized I was fortunate I had not become a teacher or professor like most of the rest of my family. It turns out my concern was well-founded: within a few years, there has already been evidence that 11 percent of assignments by students show significant use of AI-generated content, and 56% of college students say they use AI to write their papers.4

Rapid Adoption

I adopted AI quickly. But I was not alone. Because everyone now has a computer in their pocket, and because of the internet itself, the advent and adoption of AI developed at an entirely different pace than the previous two revolutions I've highlighted in my tech memoirs here. ChatGPT became the fastest-growing consumer application in history. Netflix took three and half years to reach 1 million users. Twitter took two years. Spotify made a big splash in its adoption in 2008 and reached a million in 5 months. ChatGPT only took 5 days. That December of 2022 was a heady one for the Open AI app. It was visited more than 264 million times that month alone.

The subsequent growth has been likewise astonishing. In February of 2025, ChatGPT was already being accessed 5.2 billion times, by half a billion unique users a month, and is already the 8th most visited website worldwide. This all grew while other AI apps and services proliferated like bunnies in springtime, certainly taking away some of the "first to market" shares of Open AI.

In the days that followed, I began to test out just what LLMs could do and applied it to all kinds of areas in my life in measured bits. I experimented with A.I. image generation, even entering some text from some fiction I was writing to see if it could imagine that world. I asked LLMs to give me synopses of books and articles that I didn't want to read but felt like I should be aware of the content of. Later on, when NotebookLM came out, I had it create à la carte podcasts out of thin air based on PDFs of books and articles I wanted to learn about but didn't have the time to read.

But all work and no play makes AI Dave a dull boy. I also had some fun along the way. I laughed at images with mangled human hands (remember when AI just couldn't pull that off or accurately put text on an image?) I loved watching early AI-generated trailers of fake movies that were pretty funny and almost like a spoof of what we watch. For giggles, I pushed different LLMs to talk about sensitive subjects, like their opinions about religion, politics, gender, and drugs. At one point, I even asked one what it thought of Kanye West as he had done some pretty controversial stuff. I laughed when early AI generation and LLMs would mess up and make the news for hallucinating things that don't exist, and I shook my head when I found out an attorney was sanctioned by a judge for citing legal decisions that didn't exist. The LLM had made them up out of thin air and convinced the lawyer to pass it off as real.5 Turns out it’s not just tenth graders who cheat.

Percival Fairchild III

Perhaps the most eye-opening early experience for me came from Rob Laughter, an acquaintance of mine from a group of leaders using AI from the start. He supplied us with a link to a podcast with an interesting hook. It was a British host with a very uppity tone talking about very mundane food items like Bubble Gum, Candy Corn, and PB&J. In the very first episode, the earnest host said, "A common yet enigmatic delight from the corners of American comfort food, the humble box of Rice Krispies Treats. Looking upon the box, one is immediately drawn to its bold blue aesthetics, embossed with its iconic trio, Snap, Crackle, and Pop. Each is as charming and perpetually jubilant as the last." Later on, the British critic exalts in his first bite, detailing how the "...distinguished crunch reverberates like a sonorous waltz, echoed by the crackling voices of the aforementioned trio of elves."

The podcast was short, funny, utterly ridiculous, and yep, you guessed it, entirely made by AI. Because AI has progressed so much in the last two years, it may not be surprising to you to hear of this now, but in May of 2023, when it came out, the podcast blew my freaking mind. I sent it to many of my friends without telling them how it was made, only to break the news after and blow their minds as well.

Rob had used AI to create a fictional host persona named Percival Fairchild III. ChatGPT and Midjourney helped him complete a backstory along with a show name and description, and a script and intro for the first episode. He then used ElevenLabs and Adobe Podcasts to create the audio, Canva AI to create the cover art, and Anchor to automatically publish it on Spotify. What blew my mind, even more, was that he did all this with an automated process to continue the podcast in perpetuity without human tending. The podcast continues to this day, with an episode on "Spreading the Charm of Chunky Peanut Butter" dropping three days ago. The amount of smiles per minute this charming and silly podcast has given me might be #1 of all the podcasts I subscribe to--and it isn't even a real human being making me smile (well, sort of, Rob Laughter is behind it, but I pay no attention to the man behind the Percival Fairchild III curtain.)

Getting Serious

While most of this was fun and games, I started to take AI a little more seriously about 3 months into using it. I started to get deep into an idea about AI that was capturing my imagination. What if artificial intelligence could be a game changer for early evangelism and disciple-making? I drafted a white paper on the subject and circulated it among a few in the world that it might connect with. I won't go deeply into it, but I'll explain the core idea.

I suggested in that white paper that what I call “Assisted Disciple-making” could be achieved by a natural language processing tool designed to facilitate the exploration of one's faith and the discovery of Jesus and scripture through dynamic conversational interactions. Distinguishing itself from conventional AI Chats, the platform would adopt an assertive approach by proactively guiding users with heightened AI prompts, resulting in a more engaging and immersive experience. The user would be presented with the opportunity to connect with real-life disciple-makers proficient in their heart language, fostering meaningful dialogues via text or video chat. The aim would be to provide a transformative journey of spiritual growth initially powered by infinitely scalable AI assistance. That's just the kernel of it, and I'll describe in a future entry where that idea led me, the people I met, and the programs I tested because of it. For now, just know that I began to take AI quite seriously.

Cultists and Prophets

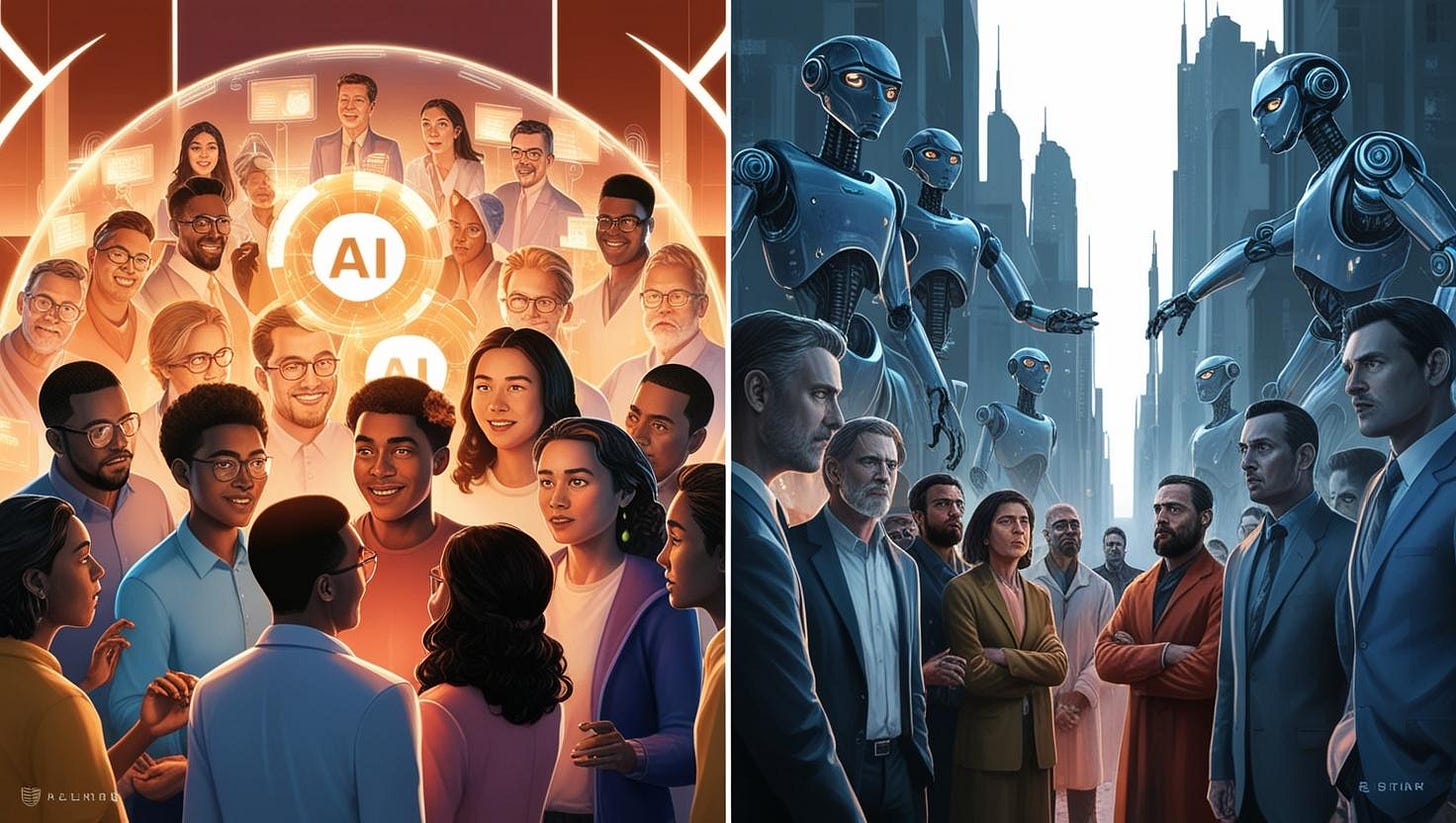

Because of the rapid adoption of AI, and likewise, because of my interest in the field, I encountered two groups of people who have polar opposite views of AI. I call them the AI Cultists and the AI Prophets.

The AI Cultists are those people who think that AI is going to solve most, if not all, of the problems of humanity. They say AI will become the standard way that everything gets done and that every single person on the planet should find a way to use AI in their work and personal life because those who don't will be so left behind that it will be like they missed a step in the evolution of the human species. This group envisions a future artificial intelligence-powered utopia that makes all things new. They say that all things that may stand in the way of AI, including questioning or doubting that it might be coming, are either ridiculous, a danger to one's future, or perhaps even a danger to others because those who might misuse AI must not be allowed to get it before we do, since we know what to do with it with our values.

The AI Prophets are the people who think AI is going to ruin most if not all of human life as we know it. They are those who say AI is going to cost us hundreds of millions of jobs, and that perhaps artificial general intelligence will at some point even destroy humanity after a season when we become unwisely dependent on it. The AI Prophets of Doom have the distinct advantage of having the majority of science fiction books and movies on their side. Those books and movies are almost invariably dystopian in their outlook about the future AI will bring upon us. Action drives movies, and there's no action if the star doesn't at some point get chased by a robot out to get him, or perhaps all the robots are out to get all of us. The AI Prophets don't think it will happen as Hollywood does, but they do believe the risk is untenably high. They want us to slow down and put limits on things, ensuring humanity is not overtaken or compromised by super-powerful AI.

The AI Prophets think everyone will eventually agree with them that the AI Cultists are greedy short-sighted betrayers of humanity, the ones all too willing to accelerate without proper assessment of the risks. Conversely, the AI Cultists think everyone will eventually agree with them that the AI Prophets are the juvenile Chicken Little types, offering street-preacher-level facile predictions to instill unfounded fear in a populace that should have just joined the AI Cult all along.

A philosophical reflection, followed by a practical one.

Philosophically, I am in agreement in principle with Neil Postman, who said "Every technology is both a burden and a blessing; not either-or, but this-and-that."6 The reality is that both the Cultists and the Prophets have a point. I think that the extreme views on each side cloud us to the key parts of the other. I hope to understand the burdens and blessings AI might bring to us shortly and in the future. Prediction is a messy profession, especially when it comes to technology. It is easy to sound a fool in the not-so-distant future. But I do think we can address these things with some measure of balance. I trust we can have a more matter-of-fact assessment of the opportunities and challenges that await us in this new era of artificial intelligence.

Stephen Vincent Benét's poem reads, "If you at last must have a word to say, Say neither, in their way, 'It is a deadly magic and accursed,' Nor 'It is blest,' but only 'It is here.'" So to both those cultists who might call it blessed and those AI Prophets who call it a deadly and accursed magic, I say that the age of AI is upon us. Let us dialog somewhere between the extremes and say only, "It is here."

One practical place to start was suggested by Kevin Roose, one of the best technology reporters out there. He offers a simple rubric for evaluating when to use an AI and when not to, which is a quandary many of us find ourselves in.7 Roose says to run the decision through the "Forklift or Weightlift" filter. A forklift is a tool to help you move heavier stuff. If you work at a place that has a forklift and you're trained to use it, then by all means, use it. It would perhaps harm you to try to move what a forklift can move, and there is no needed value in moving things that a forklift could move in much less time if you can learn to do it. It's a useful technology to speed up something hard to do. Conversely, you lift weights to improve yourself. You don't have to move that barbell in multiple sets. There isn't intrinsic value in weightlifting in the short term. However, you are building muscles and getting fit by doing so.

The metaphor works for AI, as you no doubt see. Some things that AI can do help you like a forklift. Use it to do the things that take extra time. That's helpful. But beware of using AI so much that you are no longer improving yourself. Be careful of doing the functional equivalent of driving to the gym and then having a robot lift weights for you. That makes the whole trip a waste. There are some things you should do to continue to improve; these are the things that should remain in the human domain. What are those things for you?

There are many of those for me, and an example is writing. I know many people are using AI a lot for writing. I'm not one of them. I do not use AI at all for my Substack articles like this one, for instance. These are all my words and are not created at all or in part by AI. I have chosen that limitation for myself because I want to have something that is mine--that is truly an expression of myself: my ideas and my voice. Could you subscribe to some other Percival Fairchild III-type creation of artificial intelligence that might mimic me or entertain you in my place? Perhaps.

I shrug my shoulders and keep doing what I do. I do not decry the deadly accursed magic, nor do I call it blest and turn my brain and typing over to AI.

I only say: It is here.

What was your very first experience like with artificial intelligence and large language models like ChatGPT? You might not have as extreme a view as the AI Cultists and AI Prophets described above, but which way do you lean—are you quite hopeful that AI is going to change everything for the better, or somewhat worried AI is going to do a lot of damage?

Appreciated this article. I know more prophets than cultists, and have struggled to become an early adopter of AI (too late anyway; the early adopter phase is long gone). I honestly don't see my need for AI, which creates some FOMO (like "What am I not doing with AI that I could be or should be doing?"). Additionally, the older I get the more I step away from caring, so that's interesting to me as well.

Great writing Dave (well, I think so anyway). :)

When my son, now 36, was small we asked our two children to pray for the First Family. I still laugh when I think of him praying for Bill, Hillary and Algore Clinton. We never corrected him.

A great post, and thank you.