In a previous article, I featured the work of Andy Crouch and his book, Strong and Weak. That article and the book it references include a 2x2 chart with four quadrants.

I followed that with a reflection on what we can learn from the crises of our time. But now I am intentionally featuring another leadership model below that includes a 2x2 chart quadrant (rather than a borrowed one this time, it is one I developed and have used for several years.) I'm connecting these two closer in part to point out the transferability of the method, not just the content.

I like diagrams. They are a bit of a passion for me, as it seems to be for Andy Crouch. I’ve itemized that I believe diagrams are effective because they are simple, visual, spatial, portable, and expandable. But to add to that list here, I could also claim that diagrams are eminently versatile: there are different conceptual types of diagrams to consider, and I've arranged examples into three categories below:

1. Synergy Diagrams

A matrix or Venn diagram also performs a similar function, but the 2x2 quadrants offer tidy ways to present paradoxical synergies like Crouch's Strong and Weak, and mine below on Crisis Decision-Making. I have a Venn diagram to show you soon that will focus on a blend of different sources for motivation. (A benefit of a Venn diagram is it can blend from 3 to many more dynamics, not just two.)

About his synergy-based diagram, Crouch says, "There's nothing quite as satisfying as s 2x2 chart at the right time. The 2x2 helps us grasp the nature of paradox. When used properly, the 2x2 can take two ideas we thought were opposed to one another and show how they can complement one another."

- Andy Crouch, Strong and Weak (p12)

2. Component Diagrams

Circle, tree, or pie chart diagrams help break down the component parts of a whole, helping digest these different dynamics in pieces. A triangle diagram can achieve the same intent while also providing a sense of hierarchy of importance (think: the "Food Pyramid" that circulated back when I was younger.).

3. Process Diagrams

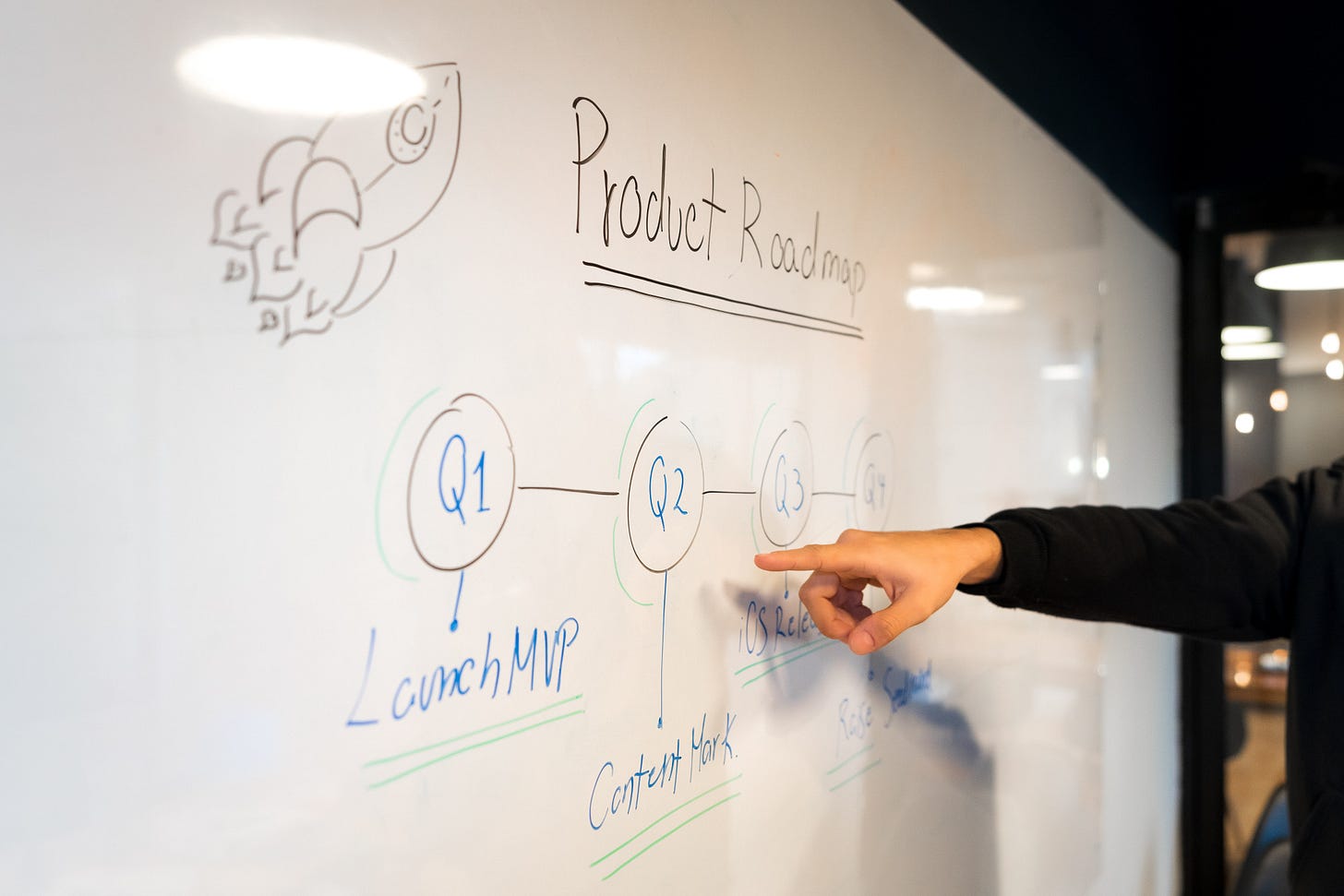

Funnel, cycle, and fish diagrams (also called Ishikawa after the creator) all communicate a process that involves stackable or phased stages. A "Gantt chart" is one of these process charts that includes dates for managing a project or event with multiple teams in different domains that inter-relate.

There are, of course, dozens of other kinds of diagrams, but these three key categories I find to be the most useful for leaders as they visualize both practical and philosophical concepts. I have found that conceptual lists are easy to forget, but diagrams stick with us.

Now, let's talk again about crisis.

The Crisis Decision-Making Quadrant features a 2x2 grid. The up/down axis represents varying kinds of desired actions. The left/right axis represents different kinds of required actions. We think of what is desired and required as coming into conflict with each other, and in some ways they indeed do, as the chart will show. But of course, there are times when they blend, and that's the focus of what leadership looks like in a crisis.

Crisis Decision-Making

From time to time leaders face a significant crisis. During the Covid-19 pandemic, many leaders experienced a sort of rolling crisis for more than a year, or it came in resurgent waves, much like the virus itself.

Some roles face more crises than others so that some become a kind of crisis-specialist. Examples of such roles are emergency room nurses, firefighters, HAZMAT removal workers, or, when you think about it, any parent of a two-year-old. However, any leader who has been in her or his position for more than a few years has faced a crisis or two (or ten).

So, the Crisis Decision-Making Quadrant is a leadership diagram that might help you the next time you face a crisis.

Tip: The best way to use this is to draw it on a whiteboard or print off the diagram only and give it to your team, describing in your own words each category. Then do a time of discussion with four boxes up on a whiteboard or flip chart and "fill in each box" with suggestions from the group of what might fit into each.

Desired Action ("Want To")

The top two boxes (Seize and Redefine) are those actions you, as a leader, desire. These are the initiatives and opportunities you want to do something about. Now, it doesn't mean other people, including other leaders, want to do them. You do.

Now, in a crisis, those who might be accused of Machiavellian motivation might have a "never waste a crisis" approach to advancing their aims. Perhaps we are all rightly skeptical of "using" a crisis environment to get done what we want to do. I understand that concern but think it is critical to know that leading in a crisis demands a different engagement from a leader. A crisis means the landscape has changed. Expectations of leaders shift. The field of play and the rules of engagement get tossed out of the window. Good leaders are always thinking of these factors in what they are leading, so it is only natural, or even good stewardship to say: "Okay, we're in a crisis. How have things changed and what must we do now?"

Tip: If you are mapping a good number of items on a quadrant, the higher the dot is on the quadrant the more desirable it is for you or your collective team. If a great number of items are placed in the discussion on the board, then it can be a useful exercise to have everyone vote on each box with a marker slash or little stickers on a flipchart, and then proceed to push those items more desired up higher on the priority list (and visually on the quadrant as well, in the meeting itself or the notes from the crisis-management meeting.)

Required Action ("Have To")

The right two boxes (Seize and Delay) are those actions you, as a leader, are required to take. A crisis often involves many immediate actions in subsequent days and weeks (or months). These are the reactive and responsive decisions made in light of the new knowledge or situation. Now, this also doesn't mean other people, including other leaders, believe these actions are required, but you believe they are (because they are the responsible actions).

Tip: You can do the same quadrant exercise from above figuring out what actions are more required (necessary) than others and put the dots farther to the right, or rank them in a linear list. The key distinction is that just because you want to do something doesn't mean it is required. It may seem so logical to you that it feels required, but you have to be honest that some things you don't have to do, you just really really want to.

So, what are your thoughts on using this diagram to discuss what is required or desired in the crisis you are facing or might face in the future? Let’s discuss it by clicking “leave a comment” below.